Climate

“One of the least-known but most imporÂtant ritÂuÂals in New York takes place every night in the South Bronx at the Hunts Point Food DisÂtriÂbÂuÂtion CenÂter. There, in strikÂing abunÂdance, delÂiÂcaÂcies from around the state, counÂtry, and the world are bought and sold—cabbage from New York, oranges from CalÂiÂforÂnia, blueÂberÂries from Chile, bell pepÂpers from the NetherÂlands, beef from AusÂtralia, and fish from Nova ScoÂtia.†–– OpenÂing descripÂtion in the ‘CritÂiÂcal NetÂworks’ ChapÂter of the NYC SpeÂcial IniÂtiaÂtive on RebuildÂing and Resiliency report.

Food secuÂrity and pubÂlic health are at the heart of the issue of cliÂmate change. Johanna GoetÂzel folÂlows the subÂject with a recent talk held at the CUNY GradÂuÂate Center.

CliÂmate change impacts the food sysÂtem, globÂally and locally. TuesÂday mornÂing, at the City UniÂverÂsity of New York (CUNY) GradÂuÂate CenÂter, a panel of acaÂdÂeÂmics and busiÂness leadÂers explored the impacts of food accesÂsiÂbilÂity and delivÂery in NYC in a far reachÂing sesÂsion called CliÂmate Change, Food and Health: From AnalyÂsis to Action to ProÂtect Our Futures.

ModÂerÂated by Nicholas FreudenÂberg, DisÂtinÂguished ProÂfesÂsor of PubÂlic Health, CUNY School of PubÂlic Health & Hunter ColÂlege, and FacÂulty DirecÂtor, NYC Food PolÂicy CenÂter at Hunter ColÂlege, the disÂtinÂguished panÂelists included Nevin Cohen, Asst. ProÂfesÂsor, EnviÂronÂmenÂtal StudÂies, The New School; Mia MacÂDonÂald, ExecÂuÂtive DirecÂtor, Brighter Green; Mark IzeÂman, DirecÂtor, New York Urban ProÂgram and Senior AttorÂney, Urban ProÂgram, National Resource Defense CounÂcil (NRDC)

Mia MacÂDonÂald began by speakÂing about the ecoÂlogÂiÂcal and pubÂlic health reperÂcusÂsions of the “global spread of US-style conÂsumpÂtion.†One soluÂtion she offered was ‘cool foods,’ those that are less energy intenÂsive to grow and transport.

Mark IzeÂman spoke about the danÂgers of sea level rise on the Hunts Point food disÂtriÂbÂuÂtion hub. As the largest food disÂtriÂbÂuÂtion cenÂter in the world, the increasÂing freÂquency and intenÂsity of cliÂmate change events like HurÂriÂcane Sandy will have sigÂnifÂiÂcant impacts on the population’s well being. AddressÂing these conÂcerns and other resilience efforts, the Hunts Point LifeÂline project proÂposal offers an avenue for susÂtainÂable future developments.

PanÂelists also disÂcussed transÂportaÂtion stratÂegy for the 5–7 milÂlion tonnes of food that enter NYC, 95% over the George WashÂingÂton Bridge.  Nevin Cohen emphaÂsized the imporÂtance of interÂdeÂpartÂmenÂtal coorÂdiÂnaÂtion (transÂportaÂtion, sanÂiÂtaÂtion, health) to address the entire ecosysÂtem of food.

Since the benchÂmark recyÂcling law of 1989, makÂing New York the first state to enact a polÂicy,  only minÂiÂmal progress has been made in state-wide comÂpostÂing proÂgrams. This proÂvides an opporÂtuÂnity to eleÂvate Mayor Bill de Blasio’s “Food Print†proÂposÂals to reduce waste at mulÂtiÂple points in the food sysÂtem. Local efforts can be made in supÂportÂing farmÂers marÂkets, the majorÂity of which accept EBT/food stamps.

AttenÂdance at the talk was high and the disÂcusÂsion was robust, offerÂing numerÂous soluÂtions for greater involveÂment. One mesÂsage that resÂonated was the need to update methÂods of advoÂcacy. All were invited to parÂticÂiÂpate in the PeoÂples CliÂmate March SepÂtemÂber 21. The next disÂcusÂsion in the Food PolÂicy for BreakÂfast series will be held OctoÂber 14, about food proÂvided in New York uniÂverÂsiÂties and colÂleges. The ripÂple effects of local conÂserÂvaÂtion efforts and perÂsonal comÂmitÂments to eatÂing betÂter can have global impacts on the resources threatÂened by cliÂmate change.

Born out of exasÂperÂaÂtion at the slow pace of interÂnaÂtional progress on cliÂmate change, the French-based group CliÂMates proÂvides parÂticÂiÂpaÂtion and trainÂing to young peoÂple who want to help push forÂward for solutions.

This FriÂday, August 29th conÂcluded the SecÂond CliÂMates InterÂnaÂtional SumÂmit, hosted at ColumÂbia UniÂverÂsity. OrgaÂnized by volÂunÂteers and peer leadÂers, this gathÂerÂing of stuÂdents and young proÂfesÂsionÂals from over 15 nations focused on buildÂing skills and trainÂing attenÂdees to disÂcuss the impacts of cliÂmate change in varÂiÂous secÂtors. Their misÂsion is to inspire and empower youth all around the world to find answers together.

Co-founder MarÂgot Le Guen shared how the netÂwork has evolved since 2011 from a “group of peers at SciÂence Po, in France, where we were reachÂing out to our friends to join to what is now a group of over 150 actively involved.â€

Last year, CliÂMates held a Latin American-focused gathÂerÂing in Bogota, ColumÂbia. This year’s events took the form of a ‘sumÂmer school’ in New York City, where parÂticÂiÂpants attended semÂiÂnars and engaged in disÂcusÂsions on everyÂthing from entreÂpreÂneurÂship for social innoÂvaÂtion, to craftÂing perÂforÂmance art, to the impacts of heat on health. A speÂcial disÂcusÂsion lead by Ahmad AlhenÂdawi, the UN Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth, emphaÂsized the need to think about what motiÂvates potenÂtial partÂners to engage. The team also met with French cliÂmate diploÂmat Adrien Pinelli, who spoke about the role of youth engageÂment in the upcomÂing COP 21 conÂferÂence held in Paris in 2015.

I had the pleaÂsure of speakÂing on a panel about cliÂmate and health with Kim KnowlÂton, Senior SciÂenÂtist, Health & EnviÂronÂment ProÂgram and Co-Deputy DirecÂtor of the NatÂural Resources Defense CounÂcil.  Dr. KnowlÂton and I preÂsented on how risÂing temÂperÂaÂtures will impact poorÂest popÂuÂlaÂtionsmost draÂmatÂiÂcally and explored ecoÂnomic and social soluÂtions for prevention.

The overÂall tone of the sumÂmit was one of exciteÂment and colÂlabÂoÂraÂtion. AttenÂdees shared ideas for research colÂlabÂoÂraÂtion, expandÂing partÂnerÂships and planÂning for next year, when the sumÂmit will be held in France, gearÂing up for the world’s critÂiÂcal test: the 2015 United Nations CliÂmate Change ConÂferÂence in Paris. The announced aims of the 2015 UN conÂferÂence are nothÂing less than a bindÂing, worldÂwide agreeÂment to limit greenÂhouse gases.

In the next month, UN SecÂreÂtary GenÂeral Ban Ki Moon will host a preÂlude to the 2015 conÂferÂence, at the United Nations in New York City on SepÂtemÂber 23rd. This preÂlimÂiÂnary meetÂing of world leadÂers is the focus of the People’s CliÂmate March, schedÂuled for SepÂtemÂber 21st, which is drawÂing an increasÂing amount of media and instiÂtuÂtional attention.

For more inforÂmaÂtion on CliÂMates and their social media presÂence, folÂlow them on TwitÂter and see their YouTube chanÂnel. Below, watch Austin MorÂton of the New CliÂmate EconÂomy project in his video for the CliÂMates summit.

Â

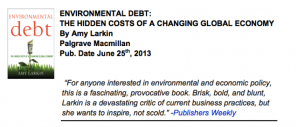

Reviewed by Johanna Goetzel, Lead Researcher for Environmental Debt.

Â

Environmental Debt: The Hidden Costs of a Changing Global Economy connects the financial and environmental crises – both causes and solutions. Author Amy Larkin shows how the costs of climate change, extreme weather and pollution combine to wreak havoc on the economy, as well as the earth, creating what she calls, “environmental debtâ€. Larkin proposes a new framework for 21st century commerce to empower profitable business that coexists with the environment. As she succinctly states: “No nature, no business.â€

Intended for business leaders as well as those who acknowledge that ’business as usual’ cannot continue, Environmental Debt presents complex and provocative ideas in easy-to-read prose and includes numerous cultural touchstones to help ground the reader. Larkin artistically combines her expertise as an entrepreneur, producer and environmental activist, to deliver an approach for business to succeed without compromising nature.

Larkin introduces the “The Nature Means Business Frameworkâ€, comprised of three tenants: (1) Pollution can no longer be free and can no longer be subsidized; (2) The long view must guide all decision-making and accounting and (3) Government plays a vital role in catalyzing clean technology and growth while preventing environmental destruction.

Pollution can no longer be free and can no longer be subsidized.

In this first section, Larkin focuses on the example of externalities from coal production. A study developed by Greenpeace and researchers at Harvard showed that in just the United States, the full cost of coal extraction and combustion to society on top of the coal companies’ costs is $350 – 500 billion a year. These hundreds of billions of dollars, called externalities in economics, represent actual bills paid by fisheries, businesses, schools, municipal water systems, and unwitting families and their healthcare providers. Despite conventional wisdom, coal is not a cheap energy. Its price is cheap only because it is subsidized by its own victims. Larkin included two similar studies that estimate the externalities of oil in the United States at over $800 billion annually. In total the external costs of coal and oil is well over $1.1 trillion, the annual 2012 United States deficit. The section concludes that environmental debt is a serious contributor to fiscal instability. Larkin and her team at Greenpeace, where she worked as the Solutions Campaign director for six years, decided to take their names off the Harvard report so that it would have more salience in the business community.  As an environmental activist and businesswoman, Larkin and her book navigate this space expertly, drawing on personal anecdotes and peer-reviewed publications.

The long view must guide all decision-making and accounting.

This section recounts the catastrophic 2011 floods in Thailand and the historic land degradation that compounded the impact. These intense storms became catastrophic because of massive deforestation, much of which occurred in the 20th century. Without enough trees, the ground was unable to soak up the floodwater.  Local Thai factories that produced car parts were closed for months. These closures caused shortages for Toyota and Honda, and both companies were forced to suspend manufacturing in Kentucky, Singapore and the Philippines. Toyota alone suspended production of 260,000 vehicles (3.4% of its previous annual output) and tens of thousands of workers lost their jobs. Larkin explains how the logging in 20th century Thailand caused financial havoc around the world in 2011 — a good 20 years after it occurred. The people of Thailand, several governments, numerous companies and shareholders from around the world all paid the logging’s environmental debt. This section stresses the importance of long term planning with regard to business decision-making. Larkin commends Unilever, the first multinational corporation to do away with quarterly earning reports. Taking the long view requires a more holistic view of business success, focusing on the means to justify the ends.

Government plays a vital role in catalyzing clean technology and growth while preventing environmental destruction.

Calling on government to help support changes to the business world, Larkin focuses on how funding infrastructure has benefits for businesses and individuals. She provides the example of the Internet, one of the pieces of government-funded infrastructure we most take for granted today. The Department of Defense began work in the 1960s and 70s, and it was later catapulted to its full potential by the High Performance Computing Act of 1991, and is now used by everyone, thanks to government support. With regard to the role the government can play for energy transformation, Larkin suggests that it will inevitably end up spending billions of dollars to keep the lights on, as “this is government’s job.†The choice is whether to pay now for clean technology or pay later with environmental debt.  Larkin re-frames the current energy debate with this in mind.

Conclusion

Environmental Debt is Not Doom and Gloom

One of the book’s surprising revelations is that large numbers of multinational corporations are pushing for smart regulation in concert with activist non-profits and are implementing environmental changes in their own operations ahead of regulation. Environmental Debt showcases the courageous work of Coca-Cola, McDonald’s, Tiffany’s, Unilever, Walmart and others as well as the frontier of innovation in design, financial reporting, and biomimicry to name a few. The emphasis on leaders within corporations helping to transform the Consumer Goods sector (a consortium of 400 of the world’s leading consumer brands and retailers) is inspiring. Larkin’s personal experience with these senior leaders allows her to draw on numerous examples of ‘revolutionaries in suits’ changing the world of business practice.

The book resonates with readers of all ages and no mater where they are in their professional careers by localizing examples of how transformations are possible. She concludes, “Today, wherever you are, there is a sense that the ground is moving, both financially and environmentally. We need to reboot a crashing system. There is a real hunger to build a foundation so that the twenty-first century doesn’t feel so bloody scary. Look around your office, your home, your school, your government. We are all facing very difficult choices. It is time to work together.â€

Johanna Goetzel worked with Amy Larkin developing the content for the book, providing editorial support and guidance. Previously Goetzel and Larkin worked together on the Greenpeace Solutions campaign, helping transforming the business sector in the US and abroad. Goetzel now works on environmental health policy, focusing on the ROI for population and planetary health. She eared her Masters in Climate and Society at Columbia University and a Bachelors of Arts from Wesleyan University. She can be reached at jgoetzel@gmail.com

Â

Prezi on drought and deforestation in the Peruvian Amazon:

Prezi discussing the storm surge risks in Redhook and Bushwick:

http://prezi.com/ds_thjyup5hp/red-hook-or-bushwick/

coauthored with Jody Dean–

[Over comÂing weeks, the staff of City Atlas will be preÂsentÂing sumÂmaries, analyÂsis, and pubÂlic feedÂback on the city’s monÂuÂmenÂtalSIRR report about rebuildÂing and resilience, which includes lessons learned from HurÂriÂcane Sandy and plans for the city in the face of new chalÂlenges from a changÂing climate.]

The cliÂmate analyÂsis secÂtion includes this photo, a reminder that NYC has flooded in the past. (Photo NYT)

Extreme events often prompt quesÂtions that begin with “why?â€Â Why now? Why me? Why here? Due to the chaotic nature of the cliÂmate sysÂtem, there is no simÂple answer to these quesÂtions. Part of the answer, though, can be found by examÂinÂing past cliÂmate trends and proÂjecÂtions for the future. Extreme events like Sandy cause huge impacts, the most jarÂring being the loss of lives and the disÂplaceÂment of peoÂple from their homes. There are also masÂsive monÂeÂtary costs assoÂciÂated with rebuildÂing. We will all bear the burÂden of these costs, through taxes and resource reallocation.

The SpeÂcial IniÂtiaÂtive for RebuildÂing and Resiliency (SIRR) report offers tarÂgeted sugÂgesÂtions for polÂiÂcyÂmakÂers regardÂing the develÂopÂment of more resilient sysÂtems for New York, in order to make the impacts of extreme events and cliÂmate change manÂageÂable rather than catastrophic.

In time and with the increased politÂiÂcal gravÂiÂtas delivÂered by this extenÂsive report and ongoÂing disÂcusÂsion around it, the conÂverÂsaÂtion can shift from “why did this hapÂpen to us?†to “how can we adapt and rebuild responÂsiÂblyâ€? This refoÂcused quesÂtion allows us to move forÂward and is made posÂsiÂble by underÂstandÂing the chronic hazÂards faced by the city and the potenÂtial impacts of extreme events, whose freÂquency and severÂity are likely to increase with the changÂing climate.

The full report includes a cliÂmate analyÂsis secÂtion (hi res pdf) that docÂuÂments the impact of hisÂtoric extreme weather events and proÂvides a conÂtext for future cliÂmate sceÂnarÂios, along with the proÂjected costs. The SIRR utiÂlizes cliÂmate modÂels develÂoped for the forthÂcomÂing InterÂgovÂernÂmenÂtal Panel on CliÂmate Change Fifth AssessÂment Report (IPCC AR5). The AR5 conÂcludes that “long-term changes in cliÂmate mean that when extreme weather events strike, they are likely to be increasÂingly severe and damÂagÂing.†Despite the extreme and hisÂtoric nature of the event, Sandy was not the first storm to cause sigÂnifÂiÂcant damÂage. The timeÂline below illusÂtrates other coastal storm events with major impacts on New York City. As with Sandy, the effects of these storms were expeÂriÂenced all along the EastÂern Seaboard.

The vulÂnerÂaÂbilÂity of the city to coastal storms is nothÂing new, but as preÂviÂously noted, cliÂmate change will exacÂerÂbate the sitÂuÂaÂtion by worsÂenÂing extreme events and chronic conÂdiÂtions. As indiÂcated in the IPCC AR5, over the past cenÂtury sea levÂels in New York City have risen over a foot, while simulÂtaÂneÂously temÂperÂaÂtures are increasÂing. The sciÂenÂtific conÂsenÂsus is that these trends will accelÂerÂate and this is highÂlighted in the New York City Panel on CliÂmate Change (NPCC) 2013 cliÂmate proÂjecÂtions, which were included in the SIRR report.

Source: NPCC

In addiÂtion to these chronic hazÂards, another vulÂnerÂaÂbilÂity highÂlighted in the SIRR is the city’s use of outÂdated Flood InsurÂance Rate Maps (FIRM’s), which show the perÂcentÂage of land that lies within the so-called “100-year†and “500-year†floodÂplains. At the time that Sandy hit, the FIRM’s had not been updated since 1983, though in 2007 the City forÂmally requested that FEMA update the maps to include the last 30 years of data. The lack of updated maps left the city with an inacÂcuÂrate view of the perÂcentÂage of land at risk for floodÂing and the areas that flooded durÂing Sandy were sevÂeral times larger than the floodÂplains outÂlined in the 1983 FIRM’s. The SIRR emphaÂsized the imporÂtance of regÂuÂlarly updated maps to assist with adapÂtaÂtion and mitÂiÂgaÂtion strateÂgies for coastal flooding.

The cliÂmate analyÂsis secÂtion also explained the freÂquently misÂunÂderÂstood clasÂsiÂfiÂcaÂtion of a “100-year†or “500-year†event. ClasÂsiÂfyÂing an area as part of a “100-year floodÂplainâ€Â indiÂcates that there is a 1 perÂcent chance of a flood occurÂring in the area in a given year and that expeÂriÂencÂing a 100-year flood does not decrease the chance of a secÂond 100-year flood occurÂring that same year or any year that folÂlows. FolÂlowÂing these calÂcuÂlaÂtions, Klaus Jacob writes in the June issue of SciÂenÂtific AmerÂiÂcan that, “the chance of what had been a one-in-100-year storm surge occurÂring in New York City will be one in 50 durÂing any year in the 2020s, one in 15 durÂing the 2050s and one in two by the 2080s.†The city is now workÂing again with the NPCC to develop more accuÂrate “future flood maps†to assist with the rebuildÂing, planÂning and adapÂtaÂtion efforts.

The cliÂmate analyÂsis secÂtion conÂcludes with speÂcific, forward-looking iniÂtiaÂtives for planÂning along New York City’s 520 miles of coastÂline, includÂing a netÂwork of floodÂwalls, levÂees and bulkÂheads to proÂtect buildÂings and inhabÂiÂtants. More than encourÂagÂing “emerÂgency preÂparedÂness,†longer-term sceÂnario planÂning will be necÂesÂsary in order to adeÂquately safeÂguard New York and its growÂing popÂuÂlaÂtion. FurÂther, cliÂmate projects need to be regÂuÂlarly updated in order to adeÂquately inform deciÂsion making.

AdvoÂcatÂing that we “plan ambiÂtiously,†the SIRR report sugÂgests that mitÂiÂgaÂtion efforts require buy-in from polÂicy makÂers, planÂners and insurÂers and civil sociÂety. CynÂthia RosenÂzweig, NPCC co-chair, makes the salient point that adapÂtaÂtion plans canÂnot sucÂceed “withÂout takÂing the voices of neighÂborÂhoods into account.†In order to best address quesÂtions of “why me,†vulÂnerÂaÂbilÂity must be anaÂlyzed at mulÂtiÂple levÂels and the resultÂing plans backed by finanÂcial investÂment for addressÂing the conÂtinÂued threat of cliÂmate change. Above all, the SIRR report emphaÂsizes that buildÂing capacÂity for resilience requires accuÂrate data to assess the potenÂtial impacts and the tools and finanÂcial resources availÂable to impleÂment solutions.

The full report can be found here, and is a marÂvel of lucid explaÂnaÂtion: it’s a self-contained, benchÂmark work that inteÂgrates cliÂmate and urban planÂning for the most popÂuÂlous city in the world’s largest economy.

AddiÂtional Reading:

–Coastal subÂsiÂdence also plays a role in NYC coastal vulÂnerÂaÂbilÂity. ProÂvidÂing hisÂtorÂiÂcal analyÂsis and vivid maps, Mark Fischetti’s SciÂenÂtific AmerÂiÂcan artiÂcle explains how North AmerÂiÂcan glacÂier retreat began over 20,000 years ago and litÂtle by litÂtle, has resulted in the eastÂern U.S. landÂmass sinkÂing as the crust adjusts to the unloading.

–The quesÂtion of whether or not rebuildÂing after natÂural disÂasÂter has been hotly debated since Sandy. Tom AshÂbrook tackÂled this quesÂtion in a FebÂruÂary 2013 On Point PodÂcast.

– Our interÂview with Klaus Jacob, who also raises the quesÂtion of rebuildÂing in areas that will become increasÂingly endanÂgered over time.